30 Nov Fractal Pore Structures Amplify Bacterial Growth in Soil-inspired Microfluidic Environments

Soil hosts dense and diverse microbial communities that drive major ecological processes, yet the way microbes respond to the physical structure of the soil is still not fully understood. One key unknown is how the distribution of pore sizes, which stem from soil aggregates, influences bacterial growth and movement. Because natural soil is opaque and structurally complex, directly observing these interactions is challenging. A recent microfluidic study titled “Investigating the effects of soil microstructures on bacterial growth via microfluidic channels and an agent-based model” provides a controlled route to examine how pores shaped at the micrometer scale can influence microbial behavior.

“In this study, we investigated the dependence of fractally distributed pore size distributions (from micrometers to millimeters) on bacterial activity, especially bacterial growth, using a polydimethylsiloxane culture device and numerical simulations.”, the authors concluded.

To address this problem, the authors created microfluidic devices that mimic the pore geometry found in soils. Their central idea was to compare fractal pillar arrangements, which resemble aggregate-derived pore networks, with uniform pillar arrays and pillar-free controls. They complemented these microfluidic experiments with an agent-based numerical model to examine how bacterial motility and energy usage shape growth dynamics across different structural environments.

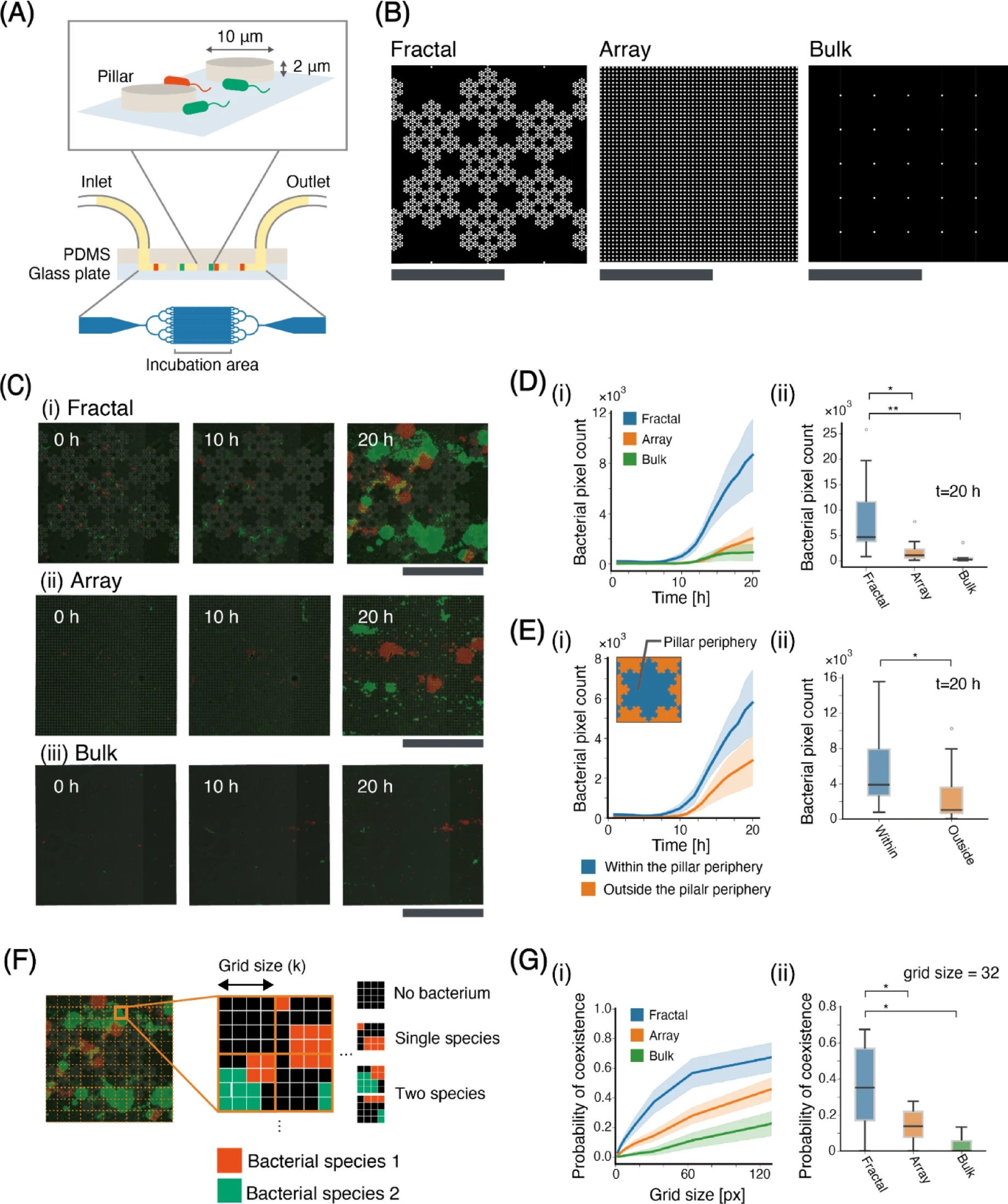

“The results of verification through microfluidic devices. (A) PDMS device designs. (B)The design of the incubation chamber. The white regions represent the pillars, while the black regions indicate regions filled with LB medium, where E. coli can move freely. (C) Snapshots of the cultivation chamber at time 0, 10, and 20 h of (i) fractal, (ii) array, and (iii)bulk arrangements. (D) Bacterial pixel count for each arrangement. (fractal: N = 9, array: N = 8, bulk: N = 5) (i) Time series of bacterial pixel count for each arrangement. Error bars represent the standard error for each arrangement. (ii) box plot of bacterial pixel count at t = 20 for each arrangement. Box plot showing the median, interquartile range (box), and potential outliers (white-filled circle). The whiskers represent data within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the quartiles. (E) Bacterial pixel count for within and outside the pillar periphery. (N = 9) (i) Time series of bacterial pixel count for within and outside the pillar periphery. In the upper-left diagram in the graph, the definitions of “within pillar periphery” and “outside the pillar periphery” are illustrated. (ii) box plot of bacterial pixel count at t = 20 for within and outside the pillar periphery. (F) the illustration of the method for calculating the probability of both species coexisting within regions with a specific grid size. (G) the probability of both species coexisting within regions with a specific grid size. (fractal: N = 9, array: N = 8, bulk: N = 5) (i) the probability of both species coexisting within regions with each grid size. (ii) the boxplot of the probability of coexisting in grid size = 32, N = 9. Scale bars: 50 μm. Statistical significance of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test is indicated by asterisks: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.” Reproduced from Ito, M., Itani, A., Suwa, A. et al. Investigating the effects of soil microstructures on bacterial growth via microfluidic channels and an agent-based model. Sci Rep 15, 40257 (2025). under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The microfluidic chips were microfabricated from PDMS and contained a 2 μm-deep chamber patterned with 10 μm radius pillars arranged in three patterns: fractal, array, and bulk. Fractal layouts reproduced the multi-scale pore distributions observed in soil cross-sections, while the array offered a uniformly spaced grid. Cultures of fluorescent E. coli were introduced into the microfluidic devices and maintained for 20 hours under static nutrient conditions. Time-lapse imaging captured how bacterial populations spread across each microfluidic structure.

The results showed substantial differences between the pillar arrangements. E. coli in fractal chambers expanded more rapidly and achieved higher cell coverage than those in the array or bulk chambers. Bacteria accumulated especially near pillar peripheries, indicating that local confinement shaped their spatial patterns. Pixel-based quantification confirmed that the fractal arrangement produced far higher bacterial counts by the 20-hour mark. Additionally, the two fluorescent strains exhibited stronger mixing in the fractal pattern compared with the array, suggesting that heterogeneous microstructures help maintain coexistence even in simple competition settings.

The simulations offered another layer of explanation. In the agent-based model, bacteria moved randomly, consumed energy while moving, and duplicated when sufficient energy had accumulated. When energy consumption was included, the fractal arrangement produced faster and higher population increases than the array and bulk patterns. The model further showed that bacterial clusters tended to form near pillar-dense regions, mirroring experimental observations. Parameter sweeps across block-like pillar patterns revealed that both the density of pillars and the size of pillar-rich regions influenced final bacterial counts, with dense and larger blocks supporting stronger growth. These findings suggested that fractal arrangements work because they mix dense and open spaces in a way that reduces excessive motility, lowers energetic cost, and improves duplication efficiency.

In conclusion, the combined microfluidic and modeling work demonstrates that pore size distribution strongly affects bacterial proliferation. Fractal pillar structures promote greater growth and stronger coexistence than uniform pillar arrays. These results highlight how pore heterogeneity can guide microbial behavior even in the absence of chemical gradients or fluid flow. Understanding such physical influences could help improve soil biophysical models and support future efforts to design materials that carry or stabilize beneficial soil microbes.

“Our microfluidic experimental and numerical simulation settings were highly simplified, focusing on the interactions between the physical structure and bacterial movement, which provided clear insights into the relationship between them. However, realistic soil is more complex, in which diverse bacteria have various social interactions (i.e., competition, prey-predator, symbiosis, and inhibition), morphologies (e.g., bacilli, cocci, and filamentous fungi), and movements. Previous reports have emphasized the importance of these features in a bacterial activity. Introducing these features into our experimental settings will provide new insights into soil bacterial activities.”, the authors concluded.

Figures are reproduced from Ito, M., Itani, A., Suwa, A. et al. Investigating the effects of soil microstructures on bacterial growth via microfluidic channels and an agent-based model. Sci Rep 15, 40257 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23995-9 under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Read the original article: Investigating the effects of soil microstructures on bacterial growth via microfluidic channels and an agent-based model

For more insights into the world of microfluidics and its burgeoning applications in biomedical research, stay tuned to our blog and explore the limitless possibilities that this technology unfolds. If you need high quality microfluidics chip for your experiments, do not hesitate to contact us.